Adriana Correa Alves

Rwanda was the scenario of one of the bloodiest armed conflicts in the modern African history. From April to July of 1994 an episode of ethnic violence between the Hutu and the Tutsi ethnical groups killed more than one million people (mainly Tutsis and moderate Hutus) in only about 100 days causing massive displacement (about 2 million people) to neighboring countries. The war and genocide took significant impact on the population structure and economy. The genocide responded to about 150,000 widows and 300,000 abandoned children. Rape and HIV infection increased in large proportions. The United Nations estimates that at least 250,000 women were raped during the genocide and a large number of those women were subsequently executed.

Although Rwanda suffered a major loss of human life during the genocide, the population size after the war remained essentially the same because over a million former refugees who were living for years in exile returned at the end of the war. Currently, Rwanda’s population structure is more stable with less displacement. People were settling fast and many are already reintegrated into the social and economic life while peace and security has been progressively assured. Many health facilities were destroyed during the genocide and even some units not affected by the conflict became without adequate staffing and equipment.

The demographic census data shows that Rwanda reached a population of 8.128,553 people in 2002 and 83% of this population was living in the rural areas. The urbanization increased substantially between 1978 and 2002. Estimated in 3.6% in 1978, the urbanization rate reached 6% in 1991 and 17% in 2002. Part of Rwanda’s population is concentrated in the capital Kigali, with 603.049 habitants in 2002 representing 44% of the country urban population. After the administrative reform of 2000 Rwanda counts with a total of 11 Provinces and the city of Kigali (see map).

Rwanda has the highest population density in Sub Saharan Africa, estimated in 321 inhabitants per square kilometer in 2002. The population is essentially young, with 67 percent of all Rwandans under the age of 20. Poverty remains a major barrier to development in Rwanda. Currently 60% of the population is below the poverty line and the poverty rates increased in the last 30 years.

The consequences of armed conflict in the size, composition and dynamics of the population are difficult to quantify. Armed conflicts often disrupt the vital statistical systems, the statistical offices and the possibilities to conduct censuses and household surveys. As a result, good and reliable data during the wartime years are usually unavailable for most countries affected by armed conflicts.

In order to present evidences about the demographic impacts of the Rwanda’s war we accessed a mix of official data sources, research findings and administrative records. Some data sources such as the Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and the National Census 2002 provide more robust demographic information. Demographic trends were built by pooling the DHS data in three moments: 1992, 2000 and 2005. The data sets covered a sample of 6,551, 10,421 and 11,321 women in the age group 15-49 years in each of these years, respectively. Details on the survey procedures and sampling design are available in individual survey reports.

The population structure by gender and age is crucial to the demographic and socio-economic analysis related with post-conflict contexts. During the 1994 war, most of deaths were concentrated in men and boys feeding the current Rwanda’s gender imbalance. The war led to an over proportion of females in all provinces, excepting Kigali city, where women represent only 46% of the population.

Figure 1 shows the Rwanda’s population distribution by age and gender in 2002. This demographic pyramid reflects the age and gender structure six years after the war. It has a very large basis and numerous irregularities in the demographic structure in several age groups as consequence of the war.

Figure 1

Rwanda Population Pyramid 2002

The pyramid base narrows rapidly as it reaches the upper age limits, indicating that fertility rates increased after the war and genocide. In 2002 the total fertility rate was estimated in 4.1 children per women in reproductive age. It indicates a resumption of previous procreation patterns following the reconstitution of the families and new unions’ formation. However, general mortality is still high. The total mortality rate in 2002 was estimated in 154 deaths per thousand inhabitants.

It is important to observe an unexpected irregularity in the number of children in some specific ages such as one, three and four years old. It could be attributable to an-over mortality lead by malnutrition and transmissible diseases in some bad years due to waves of famine and epidemics in the post-war context.

There is a significant population fall-off in the ages between 6 and 12 years old, indicating that the generation born in the war period (1990-1996) was affected by an over mortality (probably due violence and the lack of water, sanitation, nutrition and health care) and by the decrease in the fertility rates following the separation of the couples during the war. On the other hand, the disproportionately increase in the population between 11 and 20 years old is associated with the massive return of refugees which were sheltered in other countries during the wartime.

The huge gender imbalance produced by the war could also be observed in all ages at the demographic pyramid, but more extensively among the populations over 45 years old with an excess of women due the over-mortality of men during the war.

The sex ratio (measured as the proportion of men per women) is an indicator to evaluate the demographic balance between males and females. According this indicator Rwanda had 91 men for 100 women in 2002, mostly due by the effects of war and genocide. In urban areas the proportion of men is higher, but the inverse is observed in rural areas where the ratio reached 87.5 men per 100 women in 2002. The urban/rural differences in the sex ratio resulted mostly from the farming exodus of the mainly masculine populations in search of education and job opportunities in the cities, sometimes hopeless, contributing to inflate the urban poverty .

At the provincial level, sex ratios in 2002 oscillated between 87.1, in the Province of Kibuye, and 93.3, in Umutara. Inversely, in urban areas as the city of Kigali, where the male population is predominant, the sex ratio reached 117.5 in 2002.

Figure 2 represents the sex ratio at national level by residence - urban and rural - and age. The total sex ratio is bellow 100 in all age groups of 20 years old and more. This reflects the impact of war and genocide in 1994 that caused higher levels of male mortality in adult ages and mass emigration of males to neighbor’s countries.

Figure 2

Sex Ratio according age groups and residence area - Rwanda 2002

On the other hand, in urban areas the sex rate reaches an over proportion of males between the ages 20 and 60, as result to a massive demand for job opportunities by the male population.

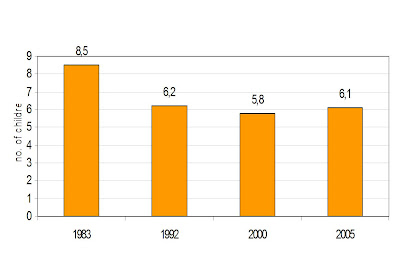

Fertility in Rwanda plays an important role on population growth. Socio cultural values, mostly linked with conservative interests defend a pro-natality attitude. The data from DHS 2005 shows that the total fertility rate (TFR) among Rwandan women remains very high: 6.1 children for women in reproductive age, 4.9 in urban areas and 6.3 in rural areas. Data also shows that after the war context, between 2000 and 2005, TFR increased from 5.8 to 6.1 (figure 3) breaking a historic context of fertility decreasing experienced since the early eights.

Figure 3

Total Fertility Rates in Rwanda: 1983-2005

Existing literature explores the hypothesis of fertility decline during periods of armed conflicts, but does not discuss what happens after the conflict. As can be shown, the TFR in Rwanda was reduced during the war period (from 6.2 in 1992 to 5.8 in 2000), increasing again in the after-war period, when TFR returns to 6.1 in 2005. The analysis of the age specific fertility rates in 1992, 2000 and 2005 (Figure 4) demonstrates a similar pattern of the fertility rate: a decrease of the TFR in the ages between 25 and 39 during the period 1992/2000 and a return to an increase pattern, between 2000 and 2005, for the same age groups. So, armed conflicts lead to a fertility decline during the conflict time and to a fertility increase after the conflict. Even so, figure 6 shows a persistent decline in the fertility in the youngest (15-19) and oldest (40-49) age groups between 1992 and 2005.

Figure 4

Total Fertility Rate in Rwanda by Women Age: 1983-2005

Another interpretation to the present high fertility rates in Rwanda is associated with the persistent unwanted fertility in this country. Women in developing countries often have more children than they desire. A birth is considered “wanted” if the number of living children at the time of conception of the birth is less than the ideal number of children, as reported by the respondent. Bongaarts (1997) argues that unwanted fertility is typically higher in countries at intermediate levels of their fertility transition.

The Total Wanted Fertility Rate is the same as the Total Fertility Rate, only if unwanted births are omitted. If all unwanted births were avoided by the adequated supplies of contraceptive means for Rwanda's women in reproductive age, the TFR for Rwandan women should be 4.6 children in 2005, rather than 6.1 children. The TWFR is higher in rural areas (4.8) than in urban areas (3.6) and in the City of Kigali (3.4).

However, the data about the unwanted fertility in 1992 (before the war) is not available. If considered that the access to family planning was better in 1992 than it is in the present, probably the unwanted fertility in 1992 should be lower than in 2005. Rwanda has the second higher TFR among 12 sub-Saharan countries in which a DHS survey has been conducted since 2000. But if the reduction of the TFR between 1992 and 2005 had kept the same pattern observed between 1983 and 1992 the Rwanda's TFR probably would reach 4.6 in 2005, standing among the lowest levels in the Sub-Saharan Region on the early 2000’s. Based on that, certainly the armed conflict has an important role in the delay of fertility rate reduction in Rwanda.

Figure 5

Total Fertility Rates in 12 Sub-saharan African Countries in the Early 2000's

The age at which childbearing begins is an important demographic indicator because it has a direct effect on a women’s cumulative fertility, particularly when contraceptive means are not available. The younger a woman is when she begins childbearing, the greater her likelihood of having many children. At the same time, having children at too young an age can have negative repercussions on the mother’s health and can put her children at risk of dying. In Rwanda, in 2005, the median age at first birth of 22.0 years for women age 25 to 49 is identical to the median age observed for women the same age in the 2000.

Another important fertility indicator is the age of marriage for women. In low income countries, the women who marry earlier tend to have their first child earlier and give birth to more children, contributing to higher fertility rates. The duration of exposure to the risk of pregnancy depends primarily on the age at which women first marry. In Rwanda, where pre-marital fertility is uncommon or very low and the efforts to control fertility are not expressive, delays in marriage can cause a reduction in the number of women under risk of childbearing. The average age at first union is 20.7 years and first sexual relation is 20.3 years, which is relatively late compared with other African countries and has remained unchanged since 1992, when the median age at first union was around 20 years. On the other hand, men in Rwanda tend to marry at an older age than women. The median age for the first marriage is 25.0 years and the median age of first sex is 20.8 years. Even having the first marriage and first sexual relation later than other developing countries, Rwanda presents high fertility rates due the little space between pregnancy and the lack of contraceptive goods and services to the poor families.

Marriage remains practically the sole context of procreation in Rwanda. Among the women age group 15-49, 49 percent declared they were in a union at the time of the 2005 DHS. The proportion of never-married women decreases as age increases and it is rare to find a woman over 45 years old who has never been married (2 percent). In addition, 12 percent of Rwandan women live in polygamous households. Rwandan women tend to marry late: only 19 percent of those between the ages of 25 and 49 had married before they were 18 years old.

Of the 11,321 women surveyed in 2005 by DHS, 49 percent were in union (29 percent formal marriages and 20 percent in informal unions). The proportion of women who never married is 38 percent. Divorced women make up only 0.9 percent of women, separated women make up 9 percent, and widows are 4 percent. The proportion of never-married women has increased since the RDHS-II, from 34 percent to 38 percent.

Apparently the war does not present a strong impact in the marital status of women. The largest increase occurred in the 15 to 19 age group, of whom 90 percent were never married in 1992, 93 percent in 2000, and 97 percent in 2005 showing the trend to increase the first marriage age mentioned before. The number of married women has remained relatively stable during the last two surveys. The proportion of widowed women has dropped by half, from 8 percent in 2000 to 4 percent in 2005, given that the 2000 data was inflated by the armed conflict effect on the men’s disproportional mortality.

The second part of this article (to be published in the next post) will address the impacts of the Rwanda armed conflict in the use of contraceptive methods, infant, child and maternal mortality, orphanhood and migration.